By Robert P. Murphy

[Reprinted from the March 2014 edition of the Lara-Murphy-Report, LMR]

Back in the September 2012 issue of the Lara-Murphy Report, I tackled an older blog post by financial guru Dave Ramsey where he strongly attacked the idea of using permanent life insurance as a savings vehicle.1 Predictably, Ramsey urged his readers to “buy term and invest the difference,” and sought to show how much wiser that course of action would be. If you trusted that Ramsey was indeed doing an apples-to-apples comparison, it sure looked like only an idiot would buy a permanent life insurance policy.

Now there were plenty of things wrong with Ramsey’s analysis; I encourage the interested reader to go look up the September 2012 LMR article where I walk through them. [Republished in the January 2015 BankNotes] (And let us know if you are a subscriber and don’t know how to access old issues!) But in the present article I want to focus on just one of his claims, because (a) it is a common objection against permanent life insurance and (b) my own response thus far has been inadequate.

Specifically, Ramsey claimed that with a “buy term and invest the difference” strategy, if you happen to die (while the term policy is still in force, of course!) then your beneficiary gets the death benefit check and your estate keeps the side fund. In contrast, if all along you had been plunking your savings into a whole life insurance policy, then in the event of your death your beneficiary would only get the death benefit check—the insurance company would “keep your cash value.”

I have been explaining for years why this is a silly objection, but last summer an Infinite Banking Concept (IBC) Practitioner convinced me that I was actually giving Ramsey too much credit in my stock response. When we are thinking in terms of how Nelson Nash tells people to use whole life for “banking” purposes, then Dave Ramsey’s objection is particularly nonsensical, showing that his comparison is totally inappropriate and that he doesn’t really understand what Nelson Nash is saying.

SETTING UP RAMSEY’S COMPARISON

To be fair, let’s extensively quote from Ramsey’s blog post to make sure the reader understands where he’s coming from. Here is Ramsey comparing the use of permanent life insurance as a savings vehicle (in order to build up “cash value” in the policy), versus Ramsey’s preferred method of buying term and investing the difference in a side mutual fund:

EXAMPLE OF CASH VALUE

If a 30-year-old man has $100 per month to spend on life insurance and shops the top five cash value companies, he will find he can purchase an average of $125,000 in insurance for his family. The pitch is to get a policy that will build up savings for retirement, which is what a cash value policy does. However, if this same guy purchases 20-year-level term insurance with coverage of $125,000, the cost will be only $7 per month, not $100.

WOW! If he goes with the cash value option, the other $93 per month should be in savings, right? Well, not really; you see, there are expenses.

Expenses? How much?

All of the $93 per month disappears in commissions and expenses for the first three years. After that, the return will average 2.6% per year for whole life, 4.2% for universal life, and 7.4% for the new-and-improved variable life policy that includes mutual funds, according to Consumer Federation of America, Kiplinger’s Personal Finance and Fortune magazines. The same mutual funds outside of the policy average 12%.

THE HIDDEN CATCH

Worse yet, with whole life and universal life, the savings you finally build up after being ripped off for years don’t go to your family upon your death. The only benefit paid to your family is the face value of the policy, the $125,000 in our example.

The truth is that you would be better off to get the $7 term policy and…put the extra $93 in a cookie jar! At least after three years you would have $3,000, and when you died your family would get your savings.

A BETTER PLAN

If you follow my Total Money Makeover plan, you will begin investing well. Then, when you are 57 years old and the kids are grown and gone, the house is paid for, and you have $700,000 in mutual funds, you’ll become self-insured. That means when your 20-year term is up, you shouldn’t need life insurance at all—because with no kids to feed, no house payment and $700,000, your spouse will just have to suffer through if you die without insurance.

Don’t do cash value insurance! Buy term and invest the difference. [Bold and italics in original.]2

As I alluded to before, there are all sorts of factual mistakes and misleading statements in the above analysis. (For example, Ramsey is ignoring the riskiness of the underlying returns, and he is cavalierly dismissing the option-value of keeping the permanent insurance policy in force when the term policy expires after 20 years.) But for our purposes in the present article, I want to focus specifically on Ramsey’s claim that the life insurance company keeps your savings when you die, and only sends the death benefit check, in contrast to the buy-term-and-invest-the-difference-strategy, in which your estate gets both the side fund and the death benefit.

THE MODEST REPLY: CASH VALUE IS ANTICIPATION OF FUTURE DEATH BENEFIT

First, let me reproduce the standard way I used to deal with this particular objection that those sinister life insurance companies would “keep your cash value” when you died. Here goes:

Dave Ramsey is correct to tell his readers and listeners that when the insured dies, the insurance company just sends a check for the death benefit. It’s important to emphasize this point, because sometimes in discussions of “banking policies” that focus on the cash value, with the death benefit described as a “bonus” or “icing on the cake,” the newcomer might be misled into thinking that the life insurance company does indeed send both. So, to be crystal clear: When you die, the life insurance company only sends the death benefit check; there is no extra “accumulated cash value” check owed to you.

But there is nothing sinister going on here; this procedure follows from what the cash surrender value is. The formal definition is that the cash surrender value reflects the present discounted market value of the actuarially expected death benefit payment minus the present value of the flow of actuarially expected remaining future premium payments. If the reader studies this definition, it should be clear that as time passes, the cash value increases, because the actuarially “expected time of death” gets closer and closer, while there are fewer and fewer remaining premium payments to offset this growing liability to the insurance company. Now if and when the insured actually does die, then those actuarial projections are collapsed into the immediate payment of the full death benefit. The rising cash value was merely the (actuarially discounted) anticipation of the eventual death benefit payment, offset by the necessary premium out-flows to keep the policy in force. The cash value isn’t something laid on top of the death benefit.

When newcomers think about permanent life insurance, it often helps to use a home mortgage analogy (where term life insurance, in contrast, is like renting an apartment): When making monthly mortgage payments on a house, the homeowner “gains equity” by knocking down the remaining principal on the loan. When the mortgage is finally cleared, the homeowner receives the deed free and clear from the bank. He wouldn’t expect the bank to then give him “all of my equity in the house” on top of the deed! That would obviously be misconstruing what “equity in the house” means.

So it’s a similar pattern with permanent life insurance. With each premium payment, the policy owner “builds equity” in the policy, reflected by the rising cash value. Yet the fundamental, underlying asset is still the death benefit check that is contractually owed to the beneficiary upon death of the insured (or maturity of the policy); the rising cash value isn’t a separate asset laid on top of the death benefit. That would obviously be misconstruing what “cash value available in the policy” means.

Thus we see that there is nothing sinister or duplicitous about a life insurance company “keeping your cash value when you die.”

THE STRONGER REPLY: THERE IS A SENSE IN WHICH YOU DO “KEEP THE CASH VALUE”

To repeat, the arguments I made in the previous section were how I had been handling this particular objection for years. It served as a good way for me to teach people about the inner workings of whole life insurance (which is the plain vanilla form of permanent life insurance that Nelson Nash recommends when implementing his Infinite Banking Concept). However, after I presented this type of response last summer at our annual Night of Clarity event in downtown Nashville, an IBC Practitioner3 pulled me aside and began a series of conversations that eventually made me agree that I had been giving Dave Ramsey way too much credit.

The fundamental problem with Ramsey’s objection is that the death benefit will be higher in the “cash value” policy than in the 20-year-term policy. So he’s not really comparing apples to apples, even though he leads the reader to believe that the two strategies give the same death benefit coverage for the first 20 years.

Even with a plain vanilla whole life policy configured in the standard way for maximum death benefit and long-term accumulation (i.e. not the Nelson Nash “banking” way for maximum cash value and near-term utilization), the person using it as a savings vehicle will obviously elect to have its dividends reinvested into the policy, buying paid-up additions of more life insurance. These one-shot, fully paid up “mini” life insurance policies boost the death benefit. So with Ramsey’s numbers, even if the cash value policy and the term policy both started at Year 1 with $125,000 in death benefit, over time the cash value policy’s death benefit would begin growing, and eventually it would grow quite substantially from year to year. In contrast, by its very construction the term policy would be stuck at $125,000 in face death benefit the entire 20 years (assuming the person didn’t die).

So yes, it’s technically true that at any point in this 20-year interval, that if the person with the cash value insurance strategy dies, he’ll “only” get the death benefit, whereas the person who opted for the Dave Ramsey strategy will get the $125,000 term death benefit plus the accumulated value of the side mutual fund. But the cash value insurance strategy’s death benefit will be more than $125,000, so Ramsey’s glib analysis is obvious wrong.

Moreover, if a person configures his or her whole life insurance policy the way Nelson Nash recommends—with a sizable fraction of the actual out-of-pocket cashflow into the policy constituting “paid up additions” rather than base premium—then the death benefit starts low and rises quickly over time with each contribution. So if a person is considering what to do with, say, a $10,000 windfall, and isn’t sure whether to put it into a whole life policy versus a mutual fund, doing the former will boost the death benefit as well as the available cash value. Yes, it’s still true that when the person dies, he will “only” get the death benefit, but the death benefit will be that much higher precisely because of that earlier contribution of the $10,000 windfall into the whole life policy.

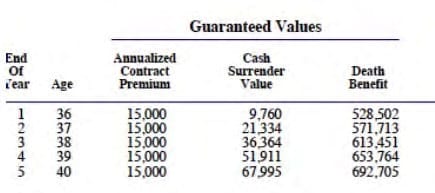

To get a specific numerical example, consider the following, which is an actual illustration from January 2013 of a whole life policy with a $4,860 contractual base premium carrying a death benefit of $373,761, but which assumes that the policyowner actually contributes $15,000 total each year—with $10,000 going toward the purchase of additional paid-up insurance. The extra $140 in premium each year funds a term policy with a death benefit of $110,000, which is necessary because of IRS rules regarding the funding of life insurance policies. Thus the initial death benefit when the contract is first signed is $373,761 + $110,000 = $483,761. Yet the table below shows, the actual death benefit—even on the guaranteed side of the illustration, which we are showing—is higher than that, and just keeps growing.

Specifically, what is happening in the above table is that each year, the owner of the policy is paying $5,000 to keep the basic policies in force ( optional contributions that buy fully paid-up insurance. This “overfunding” of the policy results in large jumps in both the cash value and death benefit. For example, going from Year 4 to Year 5, the cash value jumps by more than $16,000, while the death benefit jumps by almost $39,000. So yes, it’s technically true that if this person dies in Year 5, then he “only” gets $692,705 and “forfeits” the $67,995 in accumulated cash value that he’s been sweating to build for five years, but that hardly means his optional $10,000 contribution from the year before is flushed down the toilet. The death benefit check from the insurance company would have been much less than $692,705 had he not dumped that windfall into the policy. And remember—the above are the guaranteed values in this real-world illustration; the non-guaranteed side would have dividends that could be reinvested, too.

Before leaving the example, let’s try one more angle. Look again at the table above, and ask yourself: With these numbers, how would Dave Ramsey set up his rival strategy of “buy term and invest the difference”? In particular, what would Dave Ramsey pick as the death benefit on “the same” 20-year term policy? Would he set it to $483,761? Maybe $692,705? Some number in between? Once we realize that the death benefit on a “Nelson Nash-configured” whole life policy rises very quickly, it becomes apparent that we can’t even set up the head-to-head comparison that Dave Ramsey so glibly zoomed through in his short discussion.

CONCLUSION

In this article, I’ve picked on Dave Ramsey, but only because he is a prominent figure and because he is so scathing in his denunciations of permanent life insurance. The strategy of “buy term and invest the difference” is certainly not unique to Ramsey. Also, I should be clear that for some people, buying a term policy might make a lot of sense, particularly if they are breadwinners just starting their careers and who have young children to take care of; it might not be possible to obtain adequate death benefit coverage with a whole life policy right away.

However, the people who typically tout “buy term and invest the difference” aren’t making the modest point that it might be good for young married couples with children. No, the fans of “buy term and invest the difference” typically present an apparent head-to-head demonstration that seems to blow cash value insurance policies out of the water, thus “proving” that only an idiot would consider buying whole life insurance. As I’ve shown both in the September 2012 LMR and now in this article, their comparisons are totally inapt; these people typically don’t even understand how something like whole life insurance works.

In my 2012 article, I quickly dealt with some of the major problems in their analysis. For example, they overstate the returns on mutual funds, they ignore risk (equity-based mutual funds can crash, as happened in 2008, whereas a whole life policy’s cash value can never go down), and they blithely disregard the option-value of keeping a permanent life insurance policy in force.

In the present article, I focused on a more subtle problem, brought to my attention by an IBC Practitioner: When trying to set up “the same” term policy, these analysts must obviously pick a death benefit. Yet on a cash value policy—especially if it is designed the way Nelson Nash recommends—the death benefit of the policy will rise quickly over time. Therefore, it is a complete non sequitur—and shows just how unserious the analyst is—if he complains (as Ramsey does) that the life insurance company “keeps your cash value and just sends the death benefit.”

A whole life policy may not be appropriate for everyone, but when discussing options with a financial professional, make sure he or she actually understands how these things work. Naturally, Carlos Lara and I strongly recommend that the interested reader consult an Authorized IBC Practitioner at the website: https://www. infinitebanking.org/finder/

References

1. See Dave Ramsey’s “The Truth About Life Insurance,” October 25, 2010, available at http:/www.daveramsey.com/article/the-truth-about-life-insurance/.

2. Block quote from Dave Ramsey’s “The Truth About Life Insurance,” October 25, 2010, available at http:/www.daveramsey.com/article/the-truth-about-life-insurance/.

3. The IBC Practitioner was Jonathan Webster, founder of MPG Wealth.