Scroll to the end to download the slides

Ryan Griggs

Feb 5

I will present on the topic Why Nelson is an Heir to Menger — Reviving Austrian Capital Theory from the main stage on Wednesday, February 6, 2019. Slides for the presentation are available to view below, and I’ll release the full video and audio recording once it is made available to me.

The Context

I’m extremely thankful to the Board of Directors of the Nelson Nash Institute — David Stearns, L. Carlos Lara, Bob Murphy, and Nelson Nash — for inviting me to speak at the annual conference of Authorized IBC Practitioners and their invited guests. This is a two-day conference where the hundreds of Authorized IBC Practitioners (and their people) are invited to meet and share best practices in the business of Infinite Banking from the agent’s perspective. To be asked to share my views with the NNI membership is a career highlight for me.

The Subject

I argue in my talk that Nelson Nash should be considered an intellectual heir to the founder of the Austrian School of Economics, Carl Menger. The specific thread that ties these two men together is the subject of capital. Unfortunately, the idea of capital is fuzzy. Ask 100 people what it is, you’ll get 150 answers.

The problem of conceptual imprecision is compounded by the fact that capital theory in general is already fairly abstract, and can be straight-up confusing. However, I believe that a sound understanding of capital will not only show that Nelson Nash and his Infinite Banking Concept are Mengerian to the core, but that a good idea of capital may in fact be the key to an Austrian Theory of Finance. An Austrian Finance to mirror Austrian Economics, if you will.

Here’s the rub though. I do not think that the current view of capital among most Austrian Economists is sufficient. It isn’t that it’s totally wrong, but the emphasis is certainly misplaced.

This is what happened. In 1871 Carl Menger launched the Austrian School of Economics with the publication of his book Principles of Economics. Capital was not the subject of that book. In fact, what counts for Austrian Capital Theory today is based on a few lines in what was originally a footnote in the book (it’s a German footnote, i.e. a very long footnote, and so appears in an appendix in the current publication). In those few lines, Carl Menger calls capital the “quantity of economic goods” employed in production over time.

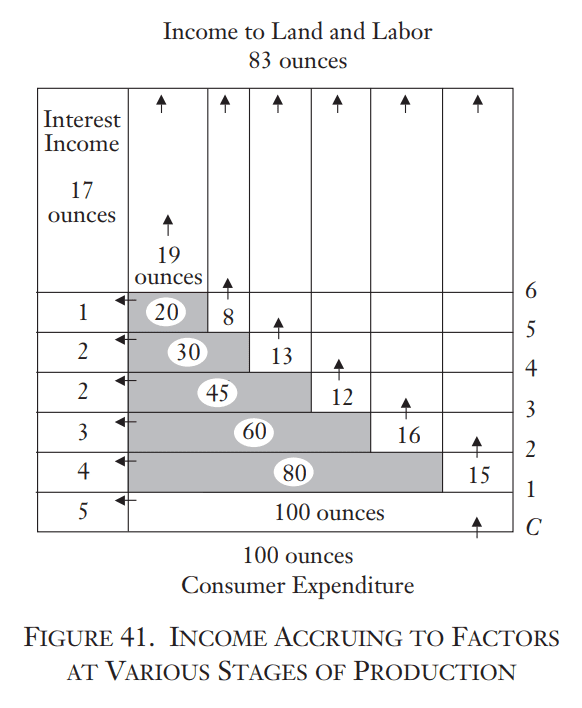

Those few lines grew up and became modern Austrian Capital Theory. Austrian Economists like Roger Garrison will argue that capital in Austrian Capital Theory is the temporal structure of production. Temporal refers to time. Production occurs over time. Some production occurs further away from the act of consumption. Other production occurs closer in time to consumption. You can group these various production activities, sequentially, according to their proximity in time to consumption.

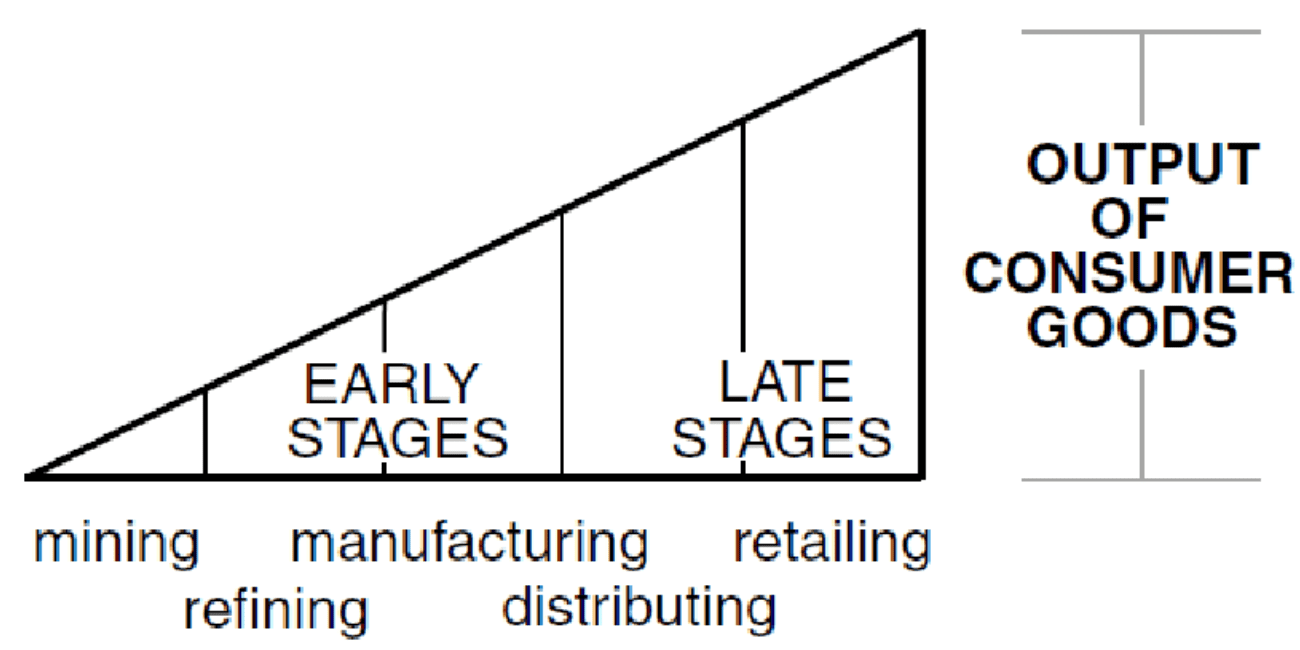

You can depict this structure in either rectangular or triangular form. In both cases, you see the various stages (or orders) of production arranged (through time) relative to consumption.

You can find this on page 369 of Rothbard’s Man, Economy, and State.

This is a rendition of the “Hayekian Triangle,” a structure of production diagram created by Professor Roger Garrison.

Regardless of the particular choice of shape, capital in this formulation is two things:

- Heterogeneous (of unlike kind), and

- Physical

The capital is the stuff. It’s the mines, the refineries, the manufacturing plants, the distribution networks, and so on. Obviously, these physical things are of unlike kind, meaning they can’t be directly compared, or grouped together, with other forms of so-called capital. You can see this if you ask, “how do we measure capital?” Under the heterogeneous, physical conception of capital, you can’t. The reason is the difference in the unit of measurement across the various orders of production. For example, a farm might be measured in acres, a delivery truck in tons, and electricity in kilowatts. Kilowatts of electricity and acres of farmland cannot be aggregated, summed up, or otherwise directly reconciled.

The heterogeneous, physical notion of capital does come from Carl Menger, founder of the Austrian School. However, the particular source is one of those lengthy German footnotes in his 1871 book Principles of Economics, and that’s basically it. The point is that modern Austrian Capital Theory — where capital is heterogeneous and physical — originates in a relatively tiny passage from Menger’s book, a book in which the subject was not primarily capital.

It turns out Menger did eventually focus on the notion of capital. In 1888 he wrote Zur Theorie Des Kapitals (or, Towards a Theory of Capital — a German version of which you can see here at Liberty Fund). However, this 1888 article is still publically unavailable in English. That’s right, over 130 years have passed since the founder of a major school of economic thought concentrated on capital, and it is still basically unavailable to the English speaking intellectual community.

Fortunately, Professor Edward Braun from Germany, who reads German and writes in English, has translated significant passages of the Menger 1888 article and published them in articles of his own. This is one of them. Braun makes the argument that Menger was pretty clear. I’m posting the Abstract to Braun’s article (linked above) here:

The common interpretation of Carl Menger’s take on capital theory rests upon a few sentences in his Principles of Economics. His later monograph on the topic, Zur Theorie des Kapitals (A contribution to the theory of capital), is more or less ignored, although it must be seen as a recantation of his earlier views. As it becomes clear in this work, Menger would have opposed all attempts to define capital as a heterogeneous structure of higher-order goods — A definition that is associated with his name today. In his opinion capital is a homogeneous concept stemming from accounting practices. The debate about Menger’s view on capital does not only concern terminological points, but involves the subject matter of capital theory. A theory of capital based on Menger’s later view would concentrate on the way the market economy is organized and not on technical characteristics of a multi-stage production process. [bold added]

What’s Braun saying here? He’s saying that when Menger turned his attention to capital, he concluded decisively that capital is not heterogeneous and physical. Instead, it is homogenous and monetary.

F.A. Hayek, who apparently was aware of Menger’s 1888 views, writes in the Introduction to Menger’s Principles of Economics that Menger thought capital was “the money value of assets with acquisitive purpose.”

For example, equity in a house that you use to purchase a car. That’s capital. The value of a bank account deposit you use to secure a line of credit. That’s capital. The cash value of a dividend-paying whole life insurance policy. That’s capital. Capital is not the house itself, the checking deposit, or the life insurance policy. Capital is the value (denominated in money) of those assets after accounting for any debt owed on them. If your house would sell for $200,000 and you owe $125,000, then your capital, your equity, is $75,000. Notice that we can actually perform calculations when we consider capital to be monetary in nature. That’s because it is homogeneous, or of a like kind. Different quantities of capital are reckoned in the same unit, like physical-heterogeneous “capital” that is reckoned in different units across the various orders of production.

In my talk I point out that this idea of capital — as homogeneous and monetary — is the key idea underneath the concept of “banking.” In order to bank, you’ve got to have something to bank with! You’ve got to have capital. And in Nelson Nash’s book Becoming Your Own Banker, where he lays out the financial strategy he calls the Infinite Banking Concept (IBC), he acknowledges this. After all, the word capital appears in one form or another 73 times in the 92-page book. In 72 of those uses, the meaning in context is obviously monetary. In the 73rd, the word stock appears in parentheses immediately after. It’s obvious that Nelson was referring to the stock or the inventory of the company in this one case. Throughout the rest of the text, Nelson Nash has a Mengerian 1888 conception of capital.

Therefore, Nelson is an intellectual heir to Menger.

In fact, you might say — as I do in the talk — that Becoming Your Own Banker is a — if not the — work in applied Mengerian capital theory.

And that is what the Infinite Banking Concept is. It’s a method to optimally build and deploy capital — capital in the sense that Menger meant it in 1888.

Next I move to what this means for financial strategy. First, we have to understand the various ways of using capital. I suggest that you can only use capital in two ways: leverage and liquidation. To deploy the equivalent of the equity in your house, you either need to collateralize it and borrow from a mortgage lender or financing company (leveraging the capital value), or you need to sell (liquidate the capital asset) and use the funds to pay off your lender and to make your purchase.

What Nelson Nash shows in Part III of Becoming Your Own Banker is that if you leverage optimally (according to the Infinite Banking Concept), you can put yourself in a powerful, prosperous position. In other words, Nelson demonstrates that leverage is preferable to liquidation (paying cash) — if done right — when it comes to using capital.

Thus, in order to benefit from capital, we need to be able to control it. When it comes down to analyzing assets to see in which it is best to build capital, we want to look at control. Does the borrower maintain control of the capital when he leverages it, or not?

In contrast, in the world of investment, it’s obvious that we explicitly, intentionally forfeit control over financial value. That’s the whole idea! The investor gives up control of financial value in order to generate cash flow, a “capital” gain (upon sale), or both. This means that capital and investment are categorically distinct.

Yet, in the financial advisory world, what do we hear about? How much of the advice from the typical financial planner is concerned with intentional, strategic capital accumulation? Effectively zero. Perversely, what little capital accumulation the financial planner does advise consists of a meager “emergency fund.” Despite the fact that the purpose of capital is to use it, we are told that what little capital we ought to accumulate (the emergency fund) we should not touch — unless of course, we have other option.

Instead, the vast majority (I mean, 98% or more) of conventional advice revolves around investment strategy. Therefore, the financial community effectively councils Americans to minimize their control over financial value. To make matters worse, the conventional planner will often advise that the individual “max out” his or her so-called tax-qualified plan. These are government-sponsored investment plans that add an additional penalty if the individual required and withdrew from the account prior to age 59.5 (in the amount of 10%). It is safe to say that not only does the financial advisory community advise minimizing control over capital, if they really had their way, the individual would drive his control over capital into the negative by suggesting that he or she should voluntarily seek and accept an additional state-mandated penalty for access to capital.

What’s the result of all this?

Answer: the vast majority of Americans are severely under-capitalized.

Americans have almost no control over their own capital. And if you don’t use capital under your ownership and control, you will rely on those who do. This is fundamentally why so many purchases in today’s economy are financed through third-party lending. Consumer debt has skyrocketed, the total value of mortgage-debt is unprecedented, as is auto-loan debt, student-loan debt, credit card debt, etc. You name it, and Americans have financed it with third-party lending.

Consequently, Americans are exposed to the cost of dependency on third-party lending. What’s this look like? It’s everything we have become conditioned to believe is acceptable. Lengthy, time-consuming applications, physical collateral assignments, use restrictions, repayment schedules, hostile bill collections departments, reliance on bank personnel relationships, dependency on bank lending policy, high interest and fees (e.g. amortization, points, etc.). Cost of dependency on conventional lending is the single greatest drain on the resources of the modern American.

And the financial community says nothing about it.

Imagine if doctors paid no attention to diet, instead focusing only on illnesses. Imagine if auto mechanics paid no attention to oil system maintenance, instead focusing only on mechanical failures. Imagine if teachers paid no attention to course content, instead focusing only on how much fun students had. You get the idea.

However, I don’t intend to neglect investment in the way conventional financial advisers neglect capital. To the contrary, with an appropriate understanding of capital, we are in an enhanced position to address optimal investment strategy.

Consider the opportunities to generate a return for two types of individuals: the under-capitalized and the well-capitalized. Let’s take the case of the majority first: the under-capitalized.

Think of the list of investment opportunities the typical, under-capitalized individual faces. First, the tax-qualified 401(k) or 403(b) options. An employer may offer a selection of 10 to 20 or so options. Each of these options is mass-marketed at least nationally, and potentially globally, thereby exposing the investor to systemic risk (this is because the modern financial system is based on the commercial lending system of fractional reserve banking — a subject for another time).

These few, mass-marketed investment options are fairly homogeneous in nature — they’re of a like-kind. Sure, the various mutual funds have varying allocation algorithms, some may be actively traded, others passively, but they’re all “in the market” to one extent or another. The actual, compounded (as opposed to average annualized) return on these options vary year to year. In 2008, many mutual funds took a proper kick in the teeth of -50%.

The conventional financial adviser will say, “well that’s alright, in general, if you stay in the market long enough, things will work out.” The idea is that in the long run, you win. Astonishingly, what the conventional financial advisory world seems to miss is the fact that in the long run, the long run becomes the short run. Look, if you’re 70 years old, how much more long run do you have to go? For an older person, the so-called long run is a lot shorter than what it is for the young person.

And pray tell, what will the market be doing in 40 years? How about 30 years? The financial elite take to the airwaves after every major market correction and plead to consumers of their “advice” that “no one saw this coming.” Well, even if that were true (it’s not), why in the world would I then want to expose my nest egg to this risk that “no one” can see coming? Maybe you’re starting to see my point.

In short, investment opportunities are few, mass-marketed, homogenous, and systemically-risky. As a special bonus, the under-capitalized is also exposed to the cost of dependency on third-party capital. Oh, and resources to engage in entrepreneurship? Forget about it. The under-capitalized employee has stacked the deck against themselves, and will most likely remain in their current industry. This presents a relatively higher degree of risk associated with a relatively high degree of labor specialization. If an individual lacks the resources (capital) to finance his or her transition to a new industry, say, when technological advancements cause increased substitution of machines and equipment for labor, then the cost of that transition will be higher. Put differently, opportunity for improvement for the under-capitalized is bad across the board.

Consider the opportunities that the well-capitalized confront. Everyone knows on some gut-level that “people with money” face a unique dilemma. The under-capitalized (those without control over financial value) will beat the door down of the well-capitalized to pitch this or that new investment or entrepreneurial opportunity. Think of the TV series Shark Tank where thousands (tens of thousands? Hundreds of thousands?) compete to get on the show and vie for the favor of the well-capitalized “sharks.” In other words, for the well-capitalized, opportunity comes to you, whereas the under-capitalized must pay all sorts of costs and accept all sorts of risk to seek out profitable investment opportunity.

Furthermore, opportunity for the well-capitalized will likely by personal, if not local or even exclusive. Maybe the investment opportunity is investing in your friend’s business. Maybe your neighbor is thinking of selling his perfectly rentable house. Maybe you and a co-worker are thinking of breaking out on your own. Whatever it may be, the likelihood for personal interaction between investor and investee produces the potential for trust, be it through past experience or the expectation of future, repeat interaction. Does the under-capitalized mutual fund investor know and trust his fund manager? Not likely. Even if he did, mutual fund managers turn over, on average, every five years, so even if he did know one manager, what’re the odds he will know the next one, or the one after that?

Finally, unique, local, trust-based investment opportunities are also relatively more likely to be highly profitable. An investment in a company that doesn’t exist yet, will generate much higher returns to the investor than one in your standard mutual fund. So if a “high rate of return” is really the holy grail of financial analysis, maybe we should be asking, “what is the best way to approach investing in the first place?” If we did so, we might wind up concluding that it is far better to approach investing well-capitalized.

So far, we have discussed the different views of capital: the modern Austrian view, versus the view expressed in Menger 1888. We expanded on the idea of capital as the money value of assets with acquisitive purpose. We saw that view of capital in Nelson Nash’s Becoming Your Own Banker adheres to the Menger 1888 notion. This gives us the context we need to see that the Infinite Banking Concept is simply the best way to build and accumulate capital. Then we integrated the two distinct notions of capital and investment from the perspective of a generalized financial strategy. In other words, we made up for what the conventional financial adviser neglects, i.e. the role of capital, the individual’s control over it, and how it affects our investment and entrepreneurial opportunities.

Let me clear up one thing: why is it that the IBC is the optimal method of building and accumulating capital? Succinctly put, it is the only asset in which one can build capital whereby, when collateralized, the lender of funds is also the guarantor of the collateral. See, the issue in every other lending transaction in the world is that the value of the collateral is inherently uncertain. Something is only worth what someone else is willing to pay for it, and with most assets, we don’t know what someone else in the future would be willing to pay.

Imagine if a mortgage lender could guarantee the future value of a home. Then, if the individual borrower failed to repay the mortgage, the lender could be certain that they could recoup their losses. But of course, no mortgage lender can guarantee the future value of a home, because no single actor in the real estate market can directly affect the future value of any property!

With the IBC and dividend-paying whole life insurance, this problem disappears. When you collateralize equity (called cash value) in one of these policies and receive money (in the form of a policy loan) from the lender (the life insurance company that sold the policy), the collateral (the cash value) is guaranteed by the lender (the life insurance company). It’s as if the mortgage lender really could guarantee the value of the home. If a mortgage lender could guarantee the value of a home, then the lender wouldn’t impose such high costs (in all the forms discussed above) on the borrower! This — the uncertainty of the value of collateral — is the source of the cost of dependency on third-party capital.

In other words, dividend-paying whole life insurance just so happens to offer the best terms of leverage to the individual. It offers the greatest level of control to the individual (there are other advantages too, like the tax treatment and growth guarantees, but these are fundamentally ancillary benefits). The way this manifests in practice is that the individual policy-owner/borrower doesn’t have to fill out any lengthy applications; there are no use restrictions; there are no physical collateral assignments, no repayment schedules, no bill collections departments, no reliance on bank personnel or bank lending policy, and so on. In other words, we eliminate the cost of dependency on third capital.

This means that the individual who adopts and implements the IBC eliminates the single greatest drain on his or her resources and positions him- or herself to become well-capitalized, thereby positions him- or herself to reap the benefits of the well-capitalized approach to investment and entrepreneurship.

In my talk at NNI I address some regulatory issues that agents should be aware of. The bottom line is that in the past, the life insurance industry has done a poor job of defending itself against colluding special interests. This has resulted in the implementation of unfavorable tax treatment for some life insurance contracts. Frederic Bastiat is alleged to have said (I’m paraphrasing) that “the worst thing for a good cause is not a skilled attack, but an inept defense.” As an industry, we should be aware that the past accusation that what an individual who adopts the IBC is doing is reaping “investment returns without paying investment tax” is flawed on basically every level. Instead, we should remain steadfast that, no, what the adopter of IBC is doing is becoming well-capitalized. In fact, if anything, this will position the individual to do better in the investment world and therefore pay even more investment tax.

If you’ve made it through all of the above, bravo, you’ve really accomplished something. I will release the video of my talk when it is made available by NNI staff.

Thank you for your time and attention!

Click below to view the slides that accompany this presentation.