by Doug Thorburn

The young client I recently wrote about (“Think Twice about Going West, Young Man,” American Thinker November 13, 2016) who asked whether to come to California to start his business asked a follow-up question, “Should I even bother opening ‘any’ small business?” I figured he could use a primer on the topic with all the pros and cons of being a business owner vs. an employee.

The Freedom

My experience as an Enrolled Agent tax pro preparing thousands of entrepreneurs’ tax returns over decades has given me insight into the entrepreneurial mind. Leaving out those motivated by the idea they have something unique to share with potential consumer kings, most budding entrepreneurs have two primary motivating factors to starting a business. One is the extra freedom the self-employed are perceived to enjoy. There is no boss to answer to (except the consumer-king!) and there is sometimes greater flexibility in the work schedule (sometimes not).

Half of all new businesses fail in their first few years.

The self-employed are the ultimate decision makers for their businesses and many of them want to be such. They want to be able to blame themselves for poor decisions and take credit for good ones, with full acceptance of the psychological and monetary consequences.

The fact that self-employed people often work many more hours than do most employees, including their own, may be offset by the fact that many love what they do.

And like me, many don’t like bureaucracies. (Decades ago, I found a particular distaste for unionized work places with everyone earning the same wage regardless of competence, as well as for one particular company I worked for rife with backstabbing alcoholics.)

The Money

The other primary motivating factor is the prospect of a high income for those in non-scalable (paid mostly hourly) professions or the prospect of having little limit to income for those in scalable occupations (paid without limitations as to time and labor; as Nassim Taleb puts it in The Black Swan, “a writer expends the same effort to attract one single reader as she would to capture several hundred million”). Most people with the greatest earnings, with the exception of crooked politicians and bureaucrats, are or have been entrepreneurs.

The problem in getting there is that half of all new businesses fail in their first few years. The ones that succeed are often only marginally profitable, and the few that become wildly profitable usually do so only after the owner has endured years of 18-hour days.

This may be due to the competition among the self-employed as well as between businesses in general. The desire to be self-employed is so prevalent that the supply of people who want to be self-employed may be greater than the demand for the products and services they offer. This tends to decrease the earnings of sole proprietors. I have seen many self-employed individuals who for years take home less after business expenses than their own employees do or less than they would make if they went to work for someone else. They remain in business simply to avoid being an employee.

This brings up the question of how much self-employed people earn compared to their employed counterparts. To make a fair comparison, all employee benefits must be included when calculating the earnings of employees. Such benefits include retirement plans, medical and disability insurance, overtime compensation, sick pay, vacation pay and, frequently, other benefits that larger corporations offer employees, including employee gyms, discounts on products and free lunches and training. These benefits increase the number of proprietors who would be monetarily better off as employees. It may turn out that overall earnings for employees are indeed higher.

One reason earnings can be lower for self-employed people is business ups and downs. Business owners feel recessions more quickly than employees, who are often somewhat insulated from such business conditions because corporations, especially larger ones, often don’t lay off until a moderate slowdown becomes severe.

The Knowledge

Another reason for earning less than employed counterparts is the extensive knowledge self-employed people must have to ensure success. Frequently, an employee need be expert in only one specialized field. Self-employed people, however, must be at least good, if not expert, in many fields.

They need to sell their products or services, so they have to have a good grasp of marketing and sales. They decide what must be purchased, how much and on what terms, understanding the pros and cons of countless options, so must be decent purchasing agents. They need to know what their products cost, directly and indirectly, including overhead and labor inputs, and how to analyze such costs, as a cost accountant can best do. Being both a good marketing strategist and a competent cost accountant is essential to pricing their products or services for maximum profit in the long run.

Despite the positives for owners and society, entrepreneurs are becoming an endangered species.

An all-too-common problem is pricing products or services too low for long-term business sustenance, as if business owners are afraid to earn a profit. Many people are emotionally at odds with maximizing profit, despite the fact that doing so is in the long run not only good for the business proprietor but also for society: the proprietor stays in business. And, if his profit is large enough as judged by his would-be competitors, they venture into his line of business and the supply of the product or service will increase and prices, along with profit margins, generally decline.

Often self-employed people must be secretaries and bookkeepers and, as in my case, a writer, publisher and negotiator (as when I deal with the IRS).

The self-employed must be able to do all these jobs until they can afford to hire such services—a time that usually doesn’t arrive until after they have mastered them in making their businesses survive.

In addition, they need a basic understanding of business-related fields such as finance, administration, employee relations, banking, insurance, business law and taxation, so they’ll know when to go to a specialist for help.

And besides all this, successful self-employed individuals must generally be self-motivated, confident, and well-organized.

The Hopes (mine)

I don’t mean to discourage anyone from becoming self-employed. Even with its drawbacks, I prefer to see as many people as possible in self-employment, if only for reasons connected with blame and credit for decision-making and production.

I hope that seeing a self-employed boss at work will help his employees better appreciate what he has gone through before they were hired and the challenges he faces after. Employees should realize they wouldn’t even have the job were it not for the employer, contrary to what many union heads and people in government would have us believe.

I hope, too, that a would-be self-employed person will develop a good understanding of what he must do to become successful. Too many have pie-in-the-sky dreams of glory and money, setting unrealistic goals for themselves which, in the end, thwart their success. Business planning based on full knowledge of both potentials and pitfalls can help to prevent failure and ensure success.

Entrepreneurship in the U.S.

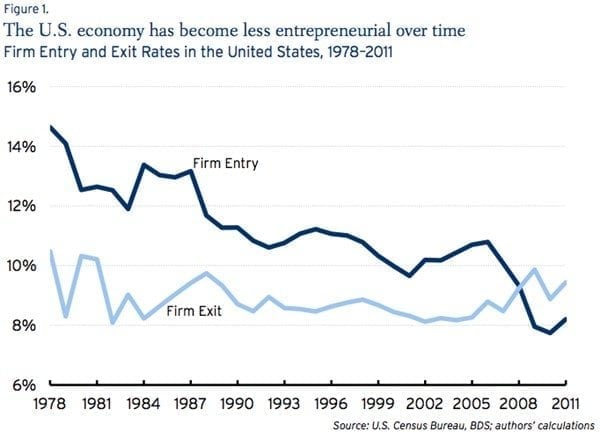

Despite the positives for owners and society, entrepreneurs are becoming an endangered species, as this chart shows:

Graph from a Brookings Institution paper, “Declining Business Dynamism in the United States: A Look at States and Metros” by Ian Hathaway and Robert E. Litan, http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2014/05/declining-business-dynamism-litan.

There are many reasons entrepreneurship has declined in the U.S. since the 1970s. One is the increase in company size in some industries, with fewer firms selling a large variety of products and services in one location such as the “big-box” store. In one trip to a Target or Wal-Mart, you can purchase a plethora of items previously purchased at several smaller stores; larger volumes allow them to offer lower prices. Costco, BJ’s and Sam’s Club have excelled at this, albeit with far less product choice, while by contrast, a small producer will struggle to out-compete a large one. Small firms do survive in niches, but there are only so many such niches.

Another reason for the reduction in entrepreneurship is increasing government intrusiveness and regulatory hurdles. Regulations are far more voluminous than three decades ago. Since 1993, more than 1.5 million pages of new federal government rules, proposed rules and regulations have been published in the Federal Register—more than 200 pages per day. This doesn’t count a massive increase in state and local rules.

Entrepreneurship suffers because the tax code is stacked against it.

The cost of compliance may be affordable for a large firm; it may be cost-prohibitive for a small one. The fact that many start-ups no longer start out small supports this idea. Daniel Hannan, a Member of the European Parliament, recently said: “The biggest surprise to me, when I was a newly elected MEP was the extent to which these giant corporations wanted more regulation. I had supposed, being elected as a conservative, that being private enterprises, they would want freedom of action. I was disabused of that within a week of arriving. They love regulation because they can afford the compliance costs more easily than their smaller rivals. They have captured the Brussels machine and used it to raise barriers to entry, very good [news] for the cartel of established multinationals, very bad news for the innovator, the startup, the entrepreneur.”

Added to compliance cost is the risk of unknowingly committing felonies in the routine course of one’s work. Harvey Silvergate makes a good case in his book Three Felonies a Day: How the Feds Target the Innocent that because of the massive number of laws we live under and their pervasive vagueness, all of us have committed felonies unknowingly, even if the ‘three’ in his book title is hyperbole.

Many owners of small firms work (at no pay) more hours than their counterparts in large firms to meet all these regulatory requirements, reducing the owner’s net income and further discouraging the number of would-be entrepreneurs. An old joke, a version of which was found in a Playboy magazine issue of some years ago, speaks to this:

A man owned a farm in Kansas. The Department of Labor received a tip that he was not paying proper wages to his employees. An agent came to interview him and said, “List your employees and tell me how much you pay them.”

The farmer said, “I have one ranch hand who’s been with me for three years. I pay him $600 a week plus room and board. Then I have a cook. She’s been here six months. She gets $400 a week plus room and board.”

“Anybody else?” the agent asked as he scribbled on a notepad.

“Yeah,” the farmer said. “There’s a half-wit here. Works about 18 hours a day. I pay him $10 a week and give him chewing tobacco.”

“Very interesting,” the agent said. “I want to talk to that half-wit.”

The farmer replied, “You’re talkin’ to him right now.”

Exacerbating the trend towards fewer entrepreneurs is high-handed government with a penchant for controlling everyone and everything. Economic fascism, in which government directs the means of production without claiming outright ownership, finds it much easier to preside over fewer, larger business than countless smaller ones. The consolidation and concomitant increase in the size of medical businesses and insurers is one case of the result: the percentage of self-employed physicians, for example, decreased from 57% in 2000 to just 36% in 2013 and is expected to hit 33% in 2016.

(Economic fascism is not Nazism. As econlib.org puts it, it’s socialism with a capitalist veneer. By this definition, we live in a largely fascist country of which Mussolini would be proud. For a terrific discussion of fascism in all its forms, see https://fee.org/articles/economic-fascism/.)

While I prefer more small businesses, the libertarian in me suggests that we simply leave the market alone to do what it will do when it is left alone.

Finally, entrepreneurship suffers because the tax code is stacked against it. Greater tax burdens are created by dramatic fluctuations in income, often the case with entrepreneurs, than by relatively equal incomes from year to year. For instance, assuming 2015 tax rates and a single filer, a sole proprietor earning $50,000 in each of two years pays total income taxes of nearly $9,500 over those two years; a proprietor earning $100,000 in one year and zero the next pays a total of more than $16,000. In another example, a sole proprietor earning $75,000 in one year and losing $75,000 the next year pays more than $10,000 in income tax plus $10,000 in self-employment (Social Security) tax in the profitable year; even with a net operating loss carryover (which allows him to offset the $75,000 profit with the $75,000 loss for income tax purposes), he’s still stuck with the $10,000 in self-employment tax; but a proprietor who earns zero in each year pays nothing.

I ran calculations for the $1 billion loss that President-Elect Donald Trump suffered in 1994. I found that using today’s tax rules and assuming he used the net operating loss carryover rules (as he should have), if he earned $1 billion in each of the next two years, his overall tax would be $57 million greater than if he had earned one-third as much (one-third-billion) in each of the three years.

While I prefer more small businesses, the libertarian in me suggests that we simply leave the market alone to do what it will do when it is left alone: serve consumers—whether customers, clients or patients—in the most cost-effective and efficient way possible. With fewer government regulations and less intrusiveness, there would likely be many more small businesses and especially start-ups, which would create a much more vibrant economy, thereby increasing productivity and hence living standards (that is, wages and net incomes).

Our economy has been sluggish, with stagnant living standards, for years. If the United States is to remain a world leader and its citizens’ incomes are to rise, the economy needs to be freed up, not increasingly strangled by people who think they know how to live our lives and spend our earnings better than we do. Hopefully the recent Republican sweep will turn this sluggish ship around by reducing the regulatory state. Perhaps now is a great time to start a business, even if it’s not in California.

Doug Thorburn, EA, CFP, Alcoholism Researcher, Author of “Alcoholism Myths and Realities” and numerous other books and articles. “Protect yourself from financial abuse.”