by L. Carlos Lara

[Reprinted from the December 2014 edition of the Lara-Murphy-Report, LMR]

There exists today a type of financial professional that is set apart from among the ranks of the three-quarters of a million licensed financial experts in the U.S. and Canada. These individuals may be attorneys, CPAs, CFPs, CLUs or even stockbrokers, but in addition to their given trade they also practice a unique financial strategy that they teach to their clients. This concept is so radically different from traditional wealth building strategies and the results so appreciably better that these practitioners are beginning to receive notable interest. The technique is so all-encompassing that it is not too far fetched to say that no other strategy will ever be needed in order to get the desired financial results. While we might begin to think that it must be some kind of exotic formula only experts can practice, we discover that what these practitioners are actually teaching their clients is a no-nonsense approach to sound cash management. It is taught to them by the founder of the idea, R. Nelson Nash (now 84) through his educational institute and school for financial professionals. The strategy is quite profound, not for the reasons we might typically assign to the work of a genius, but simply because it makes practical sense. In fact, it’s a concept with infinite cash management possibilities limited only by one’s own imagination. What Robert Murphy and I saw in our own interpretation of the concept when we first investigated its theory several years ago was the actual evidence of average Americans practicing a form of privatized banking that allowed them to achieve financial freedom. But not just average people, wealthy individuals were using it too. In light of our current economic environment and oppressive monetary policy we believe this distinctive concept should not be overlooked by anyone wishing to learn how finally to put their financial house in order— once and for all. In this Lara-Murphy Report article, I will attempt a brief explanation of what causes this uncommon cashflow management strategy and the individuals who practice it to be set apart from the rest of society that typically uses traditional financial planning systems, and why the implementation of this particular strategy requires a specific type of life insurance policy as its central piece.

Life Insurance

At this point readers may start to back up. “Life insurance? — Oh boy here we go again.” If that is your reaction you are not alone. I did exactly the same thing. As a businessman who has spent 38 years helping to solve the financial problems of closely held corporations, I asked a similar question, “What does cash flow have to do with life insurance?” Although it is absolutely true that business owners look to cash flow management with a higher degree of respect than profit and loss, I still could not make the connection to life insurance. But it’s not just the masses that push back in this way before giving Nash’s idea serious consideration. The multitudes of representatives in the financial services industry do it too, and what makes it even more difficult to teach the concept to others is that the larger part of the life insurance companies also struggle understanding it as well. Consequently, it’s difficult for them to lend credible support.

But Nash is absolutely right when he suggests using life insurance to manage your cash now and for the long term. A recent study conducted by the American Council Of Life Insurers1 revealed that 78% of Americans families own life insurance. The reason for the high percentage is that life insurance plays a vital role in the financial affairs of families as well as businesses. Not only does life insurance provide the necessary financial safety net to navigate the uncertainty of our financial future, but it is also the ideal financial instrument for business continuation plans and in estate conservation. Life insurance is the perfect tax-favored repository of easily accessible funds when the need arises, and for households and businesses that need arises quite often.

Safe and Conservative

It should not surprise any of us to learn that tens of thousands of financial professionals are engaged in the selling of life insurance, making the life insurance industry one of the largest in our economy. In the financial services industry it is matched in size by only the investment firms and commercial banks, however, the life insurance sector is much, much safer. It is not anywhere close to being as susceptible to systemic risk as the other two financial intermediaries. In a recent LMR article entitled, “Bank Deposits Are Risky, Now— More Than Ever,”2 I point out just how vulnerable we all are by simply having cash in a commercial bank account, especially since the passing of the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010. However, there is another important reason to use life insurance as one’s reservoir for cash. Statistically over the past 100 years there have been far more failures of Wall Street firms and commercial banks than life insurance companies, even during the Great Depression of the 1930s and the recent 2008 financial crisis. This is a fact that cannot be ignored.

Par vs. Non-Par

There are however, specific nuances that Nash requires for the type of policies one should use above all others. For example, Nash insists that people following his philosophy use a dividend-paying whole life insurance policy as the vehicle. Furthermore, Nash also has general advice that is not essential in every case. For example, whenever possible Nash suggests you purchase your policy from a mutual life insurance company (rather than a stock company) to implement his strategy. Unfortunately that’s not always possible. Approximately 75% of life insurers are stock companies, only 19% are mutual, or mutual holding companies and the remaining 6% are fraternal organizations. The essential difference between the two types of corporate organizations—stock vs. mutual—is ownership. Stockholders own a stock company whereas policyholders own a mutual. As to which is actually better is debatable. There are proponents of both. This is why it is very wise to work with financial professionals who have been authorized by Nash’s school to get the best advice when selecting a life insurance carrier.

The defining issue, as far as Nash is concerned, is not so much what type of life insurance company to use, but rather that the life insurance policy chassis must be able to receive dividends, or rather more specifically, be a participating (par) life insurance policy. (This is critically important since 73% of life insurance policies in force today are non-par life insurance policies.) For Nash, that explicitly means a “dividend paying whole life insurance policy.”

This one mandatory requirement, in addition to the particular design of these policies is what sets the Authorized IBC Practitioner apart from all other financial professionals who sell life insurance to individuals.

Visible vs. Invisible

As we go deeper in understanding Nash’s strategy it starts to get a little more complicated, but this is because people like me—and this includes many financial professionals—do not understand the internal workings of life insurance, except for perhaps term insurance. But remember Nash is discussing cash-value life insurance, so naturally the intellectually curious are prone to investigate all of its moving parts before purchasing it. There is nothing wrong with that human inclination except that invariably most of us get lost when trying to compare the Whole Life policy with other types of cash value policies in the industry. This is because the actuarial design of all life insurance is complex and there is no way around that issue without years of study. In fact it is one of the main disadvantages of owning life insurance. Nash knows this all too well having spent 35 years in the industry. This is why he focuses his audiences on the vision of what they are doing with the policy instead of focusing on the inner workings of the policy itself.

To make it as easy as possible to understand, he has already selected for us the main frame from which all other cash value policies are derived, and which contains the least amount of visible moving parts. In other words Whole Life is a “bundled” financial product. But this is not a negative or something to worry about; it is not missing any of its parts, they are simply invisible to the policy owner because they are fixed and guaranteed. In contrast, all other “newer” cash value policies are “unbundled” and exposed in order to make them more flexible to policy owner actions including investment actions in the equities market.

General Account vs. Separate Account

What we should clearly understand is that Nash is not only helping us make the experience of his strategy simple by selecting the Whole Life product, but is also looking out for our safety. The cash values of par whole life policies are neither determined by nor linked directly to the market performance of any underlying investments of the life insurance company’s general account. In fact, the contracts in these policies guarantee to credit the policy with a specified minimum interest rate. This is markedly different from the cash values of variable unbundled life insurance policies whose credited interest rate are determined by and linked directly to the market values of the underlying investments and are held in the “separate account” of life insurance companies. Although the investments in the separate account represent a very small percentage of the entire investment portfolio of the life company, it’s important to know that they are riskier investments consisting mostly of equities. Individuals can even choose to invest in hedge funds utilizing these policies. However, there is no guaranteed interest rate credited to the cash values of these unbundled non-par policies and the risks are borne totally by the policyholder—a characteristic not found with the par whole life insurance product.

Since dividend-paying whole life is a participating policy the policy owners share in the life insurance company’s surplus funds—that is, their profits. This is why these policies are mostly associated with a mutual company. Life insurance companies that sell this product (less than 30 out of the approximately 1,000 life insurance companies in operation today) price them so conservatively that they are nearly guaranteed to create a surplus. This surplus is returned to the policy owners in the form of tax-free dividends. You can learn the mechanics of this distribution process in my LMR article entitled, “The Divisible Surplus.”3

All Other Cash Value Policies

The Universal Life insurance policy can be thought of as a Whole Life policy that has been unbundled and made transparent to the policy owner. You not only can see all the moving parts, but a policy owner can make changes in them (within limits). It is a non-par product, although mutual companies can and do sell a lot of these policies using a subsidiary stock company. Although Whole Life was the original cash value life insurance policy, the Universal Life chassis is now the main frame for all other newer cash value permanent life insurance policies sold today. This includes Variable Universal Life (VUL) and Equity Index Universal Life (EIUL), which has gained in prominence in recent years. There are literally thousands of variations of these types of policies made to fit the various needs, risk variances and target markets found in our society. Today the Universal Life insurance product dominates the industry.

We do not mean to imply that these non-par policies are inferior to the Whole Life product; it’s just that Nash believes they are ill suited for his strategy. These other life insurance products appeal to those with greater investment savvy and who understand the volatility and longterm nature of equity markets. We would add that these individuals would not represent your average consumer and probably not even your average investment advisor. The danger of Variable Universal Life (VUL) policies is that the owner assumes the investment risk on the underlying assets, and more generally (even with the plain vanilla Universal Life) the burden is placed on the policyholder to ensure that he is putting enough money into the policy to fulfill expectations of future value. The strength of the life insurance industry historically has been its investment guarantees. With most of these unbundled, non-par life insurance policies, consumers are relinquishing these guarantees.

Once you step back and assess what is really going on with these flexible policies, the policy owner is actually being given an opportunity by the insurance company to reduce their cost of insurance (COI) charges by earning a higher interest rate. Since life insurance companies necessarily incur these various operational expenses and taxes, they must be paid via loads (charges) in the policy. As we have already made clear these loads can be bundled, fixed and managed by the insurance company, or they can be unbundled and not fixed so that consumers, who feel they are able might improve their earnings and their cash values. The methodology used can be seen in the following illustration.

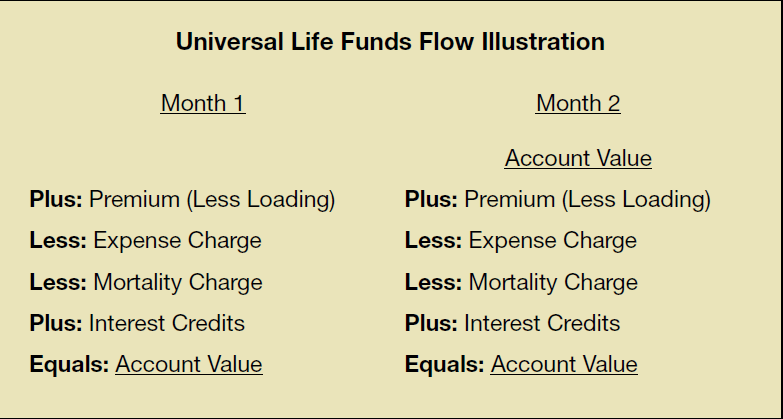

For a Universal Life policy, after deciding on the desired death benefit, the applicant must pay in a minimum premium amount to get the policy started. Thereafter, the policy owner pays as little or as much as he wants into the policy, subject to tax prescribed maximums. The frontend load is expressed as a percentage. Expense charges are stated as a flat dollar amount. The mortality charge is a dollar amount based upon the net amount at risk (NAR) to the insurance company. (Intuitively, the NAR is the difference between the cash value and the death benefit, effectively showing how much the insurer is “on the hook for” above and beyond the assets it already holds “backing up” the policy.) The monthly interest credit is applied to the account value (cash value) on a daily basis.

This process is repeated every month respecting the guarantees in the type of Universal Life policy being used. The policy remains in force only as long as the account value is positive. It will terminate if the account value goes to zero. This is the primary reason that Nash would criticize the use of these policies for practicing IBC. The buyer, especially with the passing of time, can easily misunderstand the operation, function, and sensitivity of these policies that are not Whole Life. Their safety and persistency is predicated on the policy owner’s level of life insurance expertise, discipline, and investment knowledge—attributes that are rare in most individuals. If an individual doesn’t pay close attention to, say, a Universal Life policy, it can “blow up” on him years down the road because (say) interest rates changed and the individual didn’t adjust his premium payments accordingly. The whole life policy, on the other hand, is never in danger of collapsing in this way unless the policy owner goes out of his way to abuse it. As far as flexibility goes, the participating Whole Life policy, when specially designed using dividends and special riders, can easily provide a similar flexibility feature without the risk.

Furthermore, Nash would see the cash flow management required to keep these Universal Life policies going as misplaced. The focus is all on the policy rather than the cash management that Nash is teaching in his concept. As he would put it “the need for financing the things of life is greater than the need for life insurance.” This implies that all the action happens out in the marketplace with everyday buying and selling of the big-ticket items of life. Nelson would argue that to manage the cash flow requirements of the financing function of households and businesses, a dependable, stable, guaranteed pool of money to work with is required—the fewer moving parts to worry about, the better. This is why, of the thousands of variations of cash value policies that exist today, dividend-paying whole life is ideally suited for the purposes Nash says is the essence of IBC.

Conclusion

Readers by now should not have any difficulty pointing to the distinguishable features that set the IBC Practitioners apart from everyone else in society, whether he or she is a financial professional or simply a policy owner. What we haven’t stated yet is that every financial professional who wishes to make IBC a part of his or her practice with clients and goes through Nash’s school to become authorized to do so, signs a contract with the institute. This contract binds the financial professional who promises to sell only a dividend-paying whole life insurance policy to members of the general public, under certain conditions. Specifically, though these professionals may be stockbrokers, CPAs, CLU, attorneys or other types of financial representatives engaged in selling a broad array of financial products or dispensing advice to use them, whenever clients or members of the general public specifically request a Nelson Nash, or Infinite Banking Concept (IBC) policy, only a specially designed dividend paying whole life policy can be sold to them. Individuals who make this commitment are the only Authorized IBC Practitioners recognized by the institute.

This pledge fully satisfies the Nelson Nash Institute, the institute’s board members and Nelson Nash himself that the consumer will be placed on a safe, solid foundation that cannot fail to achieve for him or her the goal of IBC—financial peace and freedom.

References

For this article I have drawn heavily from three main sources.

Life & Health Insurance, Thirteenth Edition, Kenneth Black, Jr., Harold D. Skipper, Jr., Copyright 2000, by Prentice Hall, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458 Life Insurance, Kenneth Black, Jr., Harold D. Skipper, Kenneth Black, III, Fourteenth Edition, Copyright 2013 by Lucretian, LLC, www.Lucretian.com

The Advisor’s Guide To Life Insurance, Harold D. Skipper, Ph.D., CLU, Wayne Tonning, FSA, copyright 2011, M Financial Group

1. American Council of Life Insurers, 2013 Life Insurers Fact Book, copyright 2013, Washington, D.C. https://www.acli.com/Tools/Industry%20Facts/Life%20Insurers%20Fact%20Book/Documents/Life_Insurers_Fact_Book_2013_All.pdf

2. Bank Deposits Are Risky, Now, —More Than Ever, by L. Carlos Lara, Lara-Murphy Report, May, 2014 https://s3.amazonaws.com/lmrreport/lmr_05_2014_final.pdf

3. Understanding The Divisible Surplus Of Mutual Life Insurance Companies, by L. Carlos Lara, Lara-Murphy Report, May 2012 https://s3.amazonaws.com/lmrreport/lmr_may2012_5.pdf