By L. Carlos Lara

[Reprinted from the October 2014 edition of the Lara-Murphy-Report, LMR]

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis following the crash of the stock and real estate markets, Americans witnessed 1,200 of the estimated 7,000 commercial banks in the country stagger financially. As expected the FDIC sprang into action to cover bank depositor’s funds, but what many people have never realized is that the FDIC literally ran out of money! The FDIC went $9 billion in the hole and these reserves were shored up only after receiving a loan from the U.S. Treasury. But that’s not all, in the midst of the catastrophe panicked investors of every stripe saw the typical money storehouses for retirement savings collapse with even one of the most financially sound money market funds (the Reserve Primary Fund)1 “breaking the buck.” Prompted by a flight to safety and to salvage remaining principal, millions of Americans poured huge sums of money into the insurance sector. Even the insurance industry’s foundational product, the slow and boring dividend paying Whole Life contract, saw a resurgence it had not seen in decades. When at first it seemed like there was no place left in this entire country to put one’s money, the life insurance sector—the epitome of conservatism— was left standing, just like it always had for over two centuries.

For all of those who are now on the inside of those fortresses of financial strength, but more importantly for all those who are currently contemplating coming inside, this LMR article is written with you in mind. For the latter group, this article assumes that you are already investigating the Infinite banking Concept (IBC), either because you have read Nelson Nash’s book, Becoming Your Own Banker, or our book, How Privatized Banking Really Works, or perhaps because you are currently speaking to an Authorized IBC Practitioner who has introduced you to the concept. The substance of the present article is intended to fortify your knowledge so that you can make an informed decision. I have drawn heavily from a resource published by the American Bar Association, (ABA) which has provided me with new information to share with you. The traditional life insurance textbooks used in universities rounded out the remainder of my research. For those who already own an IBC policy, this article will only serve to broaden your understanding of the financial statements of life insurance companies.

It behooves us to make clear that the Whole Life contract used to practice IBC is only one of many different types of life insurance and annuity contracts within any given life insurance company. What we specifically want to analyze here, is not so much the different financial products, but the insurance carriers themselves. This analysis must first begin with the fact that life insurers are not immune to financial difficulty. To be sure, far fewer life insurance companies than banks and investment banks got into financial difficulty during the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Great Recession of 2008; even so, careful scrutiny of a life insurance companies’ financial condition is always warranted.

The Guarantee is the promise embedded in the contract

The life insurance sector is completely different from the commercial banking system and Wall Street. Fixed within life insurance policies are long-term, intangible financial promises not found in any other form of financial product. In effect, life insurance companies are obligated to fulfill their promises as written in their contracts now, or 65 years from now. In fact, no other financial product contains guarantees and options of such potentially long durations as those found in life insurers. Obviously, a lot can happen to the financial strength of the entity that supports these promises over such a long period of time. Consequently, the financial strength and integrity of a life insurance company are more indispensible to its customers than is true of most other firms.

Like commercial banks and the securities industry, the life insurance industry is among the most heavily regulated sectors in operation today. However, unlike the commercial banks and investment banks, which are regulated by the federal government, the individual state governments oversee the insurance industry and they are the ones that provide the rules and requirements on how companies should manage their finances and the products they sell. Although we have 50 states in the union, these insurance regulations, for the most part, are harmoniously similar.

When a life company experiences financial difficulty, state regulators take a very active role in its rehabilitation or in selling off the company to financially stronger competitors to make sure all insurer promises are fulfilled. In addition, “State Guarantee Associations, support payment of policyholder benefits of financially impaired insurers. In recent insolvencies, 100 percent of death benefits and 90 percent of policy holder benefits have been covered in full.”2 Even in the case of the famous financial impairment of AIG, it is important to recognize that its financial difficulty was neither precipitated by nor related to its mainstream insurance operations. Although sections of its holding company became entangled in selling credit default swaps, AIG’s mainstream insurance subsidiaries, including its life subsidiaries, were not directly affected by the impairment of the holding company. In fact, when state insurance regulators—not the federal government—stepped in to protect the insurance assets of its policyholders, it found them entirely intact.

A Life Insurance Company is a Liability-Driven Business

In a real sense life insurers can be considered to be a liability-driven business since they take funds from individuals and businesses today to make conditional payments in the distant future. These in effect represent the promises embedded in the contract. This leads life insurers to invest in a collection of long-term assets that consist mostly of bonds. Additionally, life insurance companies tend to purchase these fixed income securities with fairly long maturities in order to match their long-term liability commitments. This conservative investment strategy of matching the duration of assets to the duration of liabilities is known as asset-liability matching. And, as one would expect, the management of life insurance companies, including their boards, have natural motivations to insure company financial strength and profitability. They understand that strong financial numbers garner decent ratings from their rating agencies, principally, A.M. Best, Fitch, Moody’s Investor Services, and Standard & Poor’s. But, they also want to avoid any undue attention and criticism from state insurance regulators. Therefore obtaining and maintaining financial strength is a priority.

What does it mean for a life insurance company to have financial strength?

To secure top rating, life insurance companies must have a strong balance sheet and operate profitably. A strong balance sheet means assets that exceed liabilities by a sufficient margin to enable the insurer to weather adverse operational and economic conditions with minimal disruption to operations and without provoking regulatory concern about the insurance company’s financial condition. This excess would be the company’s “net worth.” In insurance speak, this would be customarily called the “surplus,” or sometimes simply as “capital.” Here we should interject how life companies assemble their financial statements in contrast to other forms of enterprises. State regulators insist that insurers be measured using Statutory Accounting principles (SAP), “based on the notion that an insurer is worth only that which it can use to meet its present obligations—and those obligations (policy liabilities)—are themselves generally calculated conservatively.”3 This approach may be differentiated from the more widely used Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) that are predicated on the concept of a business being a “going concern.” This is a significant difference in that SAP rules resemble more the familiar and strict “acid test”4 in finance when analyzing financial statements of companies. Conversely, stock analysts typically use GAAP information for analyzing companies.

Can an insurance company be too secure?

This seems like an odd question to ask, yet even though policyholders want a financially strong company they also want low-cost insurance. In essence, what this really implies is that policyholders want the company to credit high interest rates to their cash values, to project low expenses and mortality charges, and/or to pay higher dividends. As you can see this creates a dilemma for management. The lower the interest rate credited and the higher the loading and mortality charges, the more financially secure the insurer will be because it builds up surplus. But it also makes for more expensive and less competitive policies, which affect their market share. Therefore, striking the right balance between maintaining a strong financial position and providing good value to policyholders is the on-going challenge of life insurance management. I specifically point out this special distinction because it might seem that the natural inclination would be for insurance companies to always aim to become and remain exceptionally strong financially, but the incentives influencing management to do so are debatable. Obviously, the first priority is still financial strength, but as we can see, there is a limit.

Examining the Life Insurance Company Portfolio

As we have already mentioned, the assets held by the insurance companies back the liabilities that arise from in-force policies. Asset growth occurs when cash inflows are greater than cash outflows. That we would agree makes perfect sense, but then we have an interesting twist in our analysis. The life insurance assets (investments) are required by state regulation to be divided between two accounts that differ in the nature of the liabilities for which the assets are being held and invested. One account is known as the “general account” and the other as the “separate account.” An insurer’s general account supports guaranteed, interest-crediting contractual obligations, such as those arising from traditional life policies including Whole Life and Universal Life products. However, the asset composition of the separate account is materially different from that of the general account. All insurers’ assets in the separate account support liabilities arising from pass-through products for which all investment risk is borne by the policyholder. These products would include variable annuities and variable life products and are usually purchased to access equity market returns. They are considered to be riskier investments than those found in the general account and state regulators permit these riskier investments because variable life policyholders have control over their asset allocation. However, it needs to be underscored that variable life policyholders must look solely to the value of the separate account were the insurer to fail. Ordinarily, the insurer itself has no obligation to these policies. For this reason buyers wanting to tap the equity markets using variable policies must pay closer attention to insurer financial strength. On the other hand, it is also important to keep in mind that though separate account assets are indeed risky, they generally represent a much smaller portion of the entire portfolio of an insurance company.

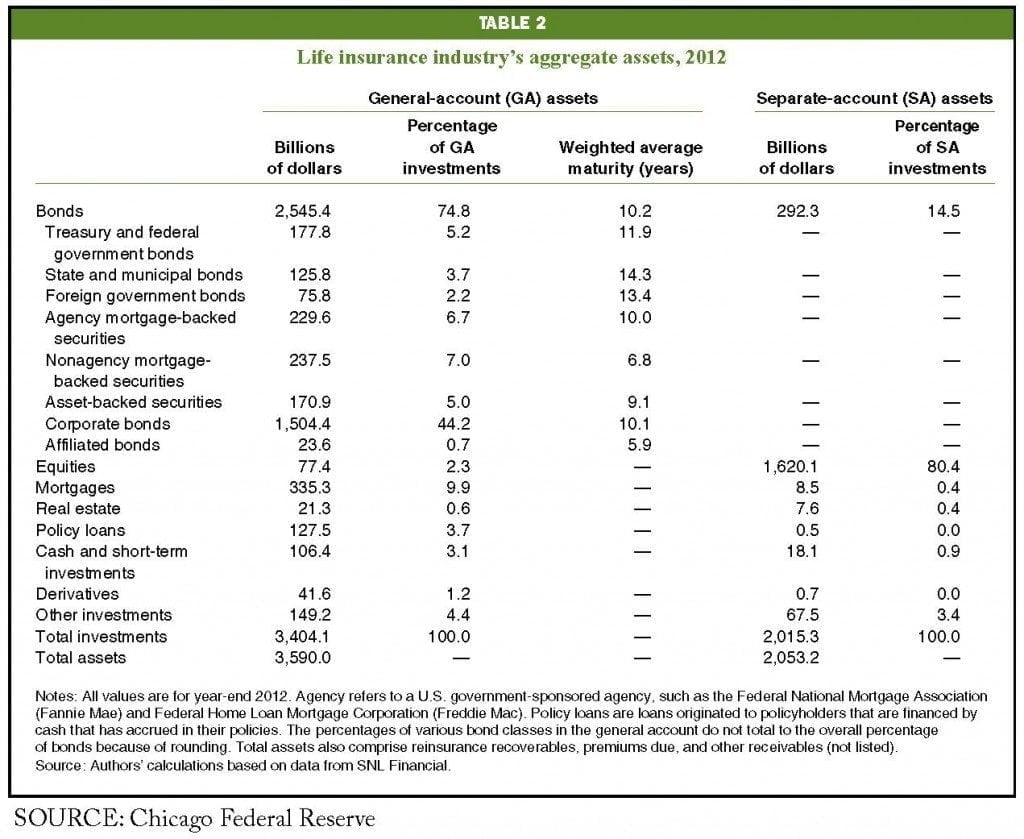

Table 2 5 taken from a recent study conducted by the Federal Reserve of Chicago on the entire insurance industry shows a broad and comprehensive overview of life insurance investments as of 2012.

Note the different category of investments and their percentages. Note also the difference and size in the General Account Assets compared to those in the Separate Account Assets. As one can see, assets in the two accounts fall into five main categories consisting of Bonds, Mortgages and Real Estate, Stocks, Policy Loans, and Cash and Miscellaneous. Notably 74.8 % of the life insurance industry’s aggregate assets are in Bonds with 44.2 % made up of high quality corporate bonds.

The traditional elements of financial ratio analysis of life companies include the following:6

1. Capital and Surplus Adequacy = Surplus/Liabilities. The higher the ratio, the greater the indication of financial strength.

2. Leverage = (Net Premiums written + Deposits) / Surplus. The higher the ratio, the greater the exposure.

3. Asset quality and diversification = Non-investment grade bonds / Surplus. Or, Mortgages in default / Surplus. The lower the ratio pertaining to these assets, the better.

4. Liquidity = Unaffiliated Investments (assets other than those in the general and separate accounts etc., less the property occupied by the company) / Liabilities. The lower the ratio, the more vulnerable is the insurer to liquidity problems.

5. Operational performance = Net gain from operations / Surplus. A high ratio can reflect excessive leverage or low capitalization.

These few ratio analyses can be helpful to those who desire to look deeper into the interrelationships of these values, however, they will not be able to show the indirect elements of a company’s market position, brand, distribution, product focus and diversification, or the competence of management. Even with this extra knowledge independent assessment of financial strength remains a complex and daunting task for everyone but the technically competent. Fortunately, the insurer provides the general public a free report, prepared by the rating agencies, that describes the rating standing of the company. If one seeks to go further and desires to obtain an independent analysis, individual company ratings can be obtained directly from the rating agencies, either by subscription to their services or purchased on a case-by-case basis from their websites.

At this point we may be asking why we should even bother with such analysis if we already own a policy and are perfectly content with what we have. It’s possible that after several years with one company a well informed policyholder may determine the company he is contracted with is weakening and feels safer moving his business to a more financially sound company or to a more suitable life insurance product. Such a move, under certain conditions, is certainly possible and is known as a 1035 exchange.7 In such a move, the carryover of the cost basis of the surrendered policy into the new one avoids recognition of any gain or loss. This is just another of the many options afforded policyholders within the life insurance industry and information everyone should know.

Conclusion

Evaluating an insurance company’s financial strength is obviously very important, but it is not simple. The purpose of this article was not to arm either the practitioner nor member of the general public with the full scope of tools for such an analysis, but rather to provide helpful background about life insurance companies that would enable individuals to better interpret and appreciate the significance of the financial information. The life insurance industry by its very nature and accounting practices is very conservative, yet it is not immune to financial reversals. Consequently, individuals looking to enter the insurance sector should, as a matter of sensible course, always look carefully at an insurance company’s financial strength as given by the rating agencies. They are available upon request. Though rating agencies are not perfect, they are the best predictors of an insurer’s financial health and buyers should place their greatest weight on their opinions.

References

1. The Reserve Primary Fund, from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reserve_Primary_Fund

2. The Advisor’s Guide To Life Insurance, Harold D. Skipper and Wayne Tonning, Copyright 2011 m Financial Group, published by ABA Publishing, Chapter 3, page 51

3. The Advisor’s Guide To Insurance, Chapter 3, page 53

4. The Acid Test, from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quick_ratio

5. The Sensitivity of life Insurance Firms To Interest Rate Changes, Berends, McMenami, Plestis and Rosen, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. https://www.chicagofed.org/webpages/publications/economic_perspectives/2013/2q_berends_mcmenamin_plestis_rosen.cfm

6. The Advisors Guide To Insurance Chapter 3, page 58-64

7. 1035 Exchange Info, http://1035-exchange.com/ October 31, 2014