By Robert P. Murphy

I spend a lot of time motivating difficult financial topics by constructing “thought experiments.” In a thought experiment, you can only focus on one or maybe two moving parts, while holding everything else constant. This is the way to isolate the impact of the factor you want to understand. However, it means the whole exercise is necessarily unrealistic.

That’s why people respond more when someone tells them an actual story about something that happened, relevant to the topic. Effective speakers know this. A polished preacher, for example, can connect even with a cynical atheist by telling an anecdote that illustrates something fundamental about human nature.

For these reasons, I thought it might be worthwhile to explain why I recently cashed out my 403(b), and used the proceeds to (among other things) buy some more paid- up additional whole life insurance and some Bitcoin. Since my moves fly in the face of conventional financial counseling, I thought it would be useful to explain some of the major considerations in my decision.

It should go without saying that I’m not offering formal investment advice in this essay. I’m just explaining why I did what I did, and letting the reader take any of my remarks into consideration when planning for the future.

Why I Had It

I first should explain why I started out with a decent amount—just so you have some idea, it was more than $15,000 but less than $75,000—in a 403(b). The simple explanation is that part of my compensation package for a spell in academia was a mandatory contribution to the tax-qualified retirement accounts designed for the educational sector. (It’s basically a 401(k) for teachers.)

Now even within this framework, I should mention that I was unusual: I had everything in either gold mining stocks and Treasuries, with the portfolio heavily weighted to the gold. When I first set it up that way, the guy from Fidelity was doing his best to lecture me about the benefits of diversification. (As a PhD economist, believe it or not, I was familiar with this concept.) I told him I had other assets filling out my desired overall portfolio—here I was primarily thinking of my existing IBC policy—and so my 403(b) was helping to check the box of, “Hedging myself against significant price inflation.” And after my 403(b) appreciated some 20% in the first year, the guy from Fidelity never bothered me again about it.

Liquidity

However, I recently left academia (for family reasons) and am focusing more on entrepreneurial ventures. As such, I wanted to enlarge my pool of liquid funds. I wanted to free myself to focus on the most productive projects, rather than being forced to pick projects that would yield their fruits in the near-term.

In short, I wanted to increase the liquidity of my portfolio, and having a pile of wealth sitting in a 403(b)—when I’m in my young 40s—wasn’t very useful to me. Because of the various enterprises I’ve set in motion, I am not worried about my long-term solvency. However, my immediate need for liquidity was pressing.

This is why I resolved to withdraw the full amount from my 403(b), in order to bolster my checking account, make a significant purchase of Paid-Up Additional life insurance, pay down some important debt, donate to the church, and to buy some Bitcoin.

I’m not going to do justice to the explanation for why I used the money the way I did.

Carlos and I outlined our economic prognosis and why we thought people should acquire actual cash (currency in the home vault), an IBC life insurance policy, and gold/silver coins in the video presentation, “How to Weather the Coming Financial Storms,” available at: https://lara-murphy.com/video0916/.

For an explanation of what Bitcoin is and how it works, see the guide I co-authored with Silas Barta, available at: www.UnderstandingBitcoin.us

In the remainder of this article, I’ll try to explain why I decided to get out of my 403(b).

Borrow?

I’m not going to summarize the nuances here, but suffice it to say, if you want to borrow against your 403(b) or other tax-qualified retirement account, there are incredibly onerous payback rules. Basically, they only let you use your money if you don’t need it.

So although I initially thought I would just temporarily put my gold mining stocks on hold, when I saw the actual rules I decided it made more sense just to liquidate the whole thing, period. I can buy gold mining stocks down the road if I want them again.

Tax Implications

The most obvious objection people raise to my decision is the tax implications. First, I had to pay income tax on my withdrawal. Second, I had to pay a 10% penalty because it was an unauthorized early withdrawal.

Let me just stop and observe, that this is really screwy. It is a sick joke that the United States federal government—which is anywhere from $40 trillion to $200 trillion in debt, depending on how we evaluate the promises made via Medicare—is spanking people if they have the audacity to try to use their own wealth earlier than the government deems appropriate. If for no other rea- son than to withdraw consent, I had an urge to get out of this paternalistic system.

However, we can put aside ideological considerations and just look at the numbers. If we for the moment set aside the penalty, the simple fact is that—holding everything else, like annual income and the tax code, constant—it is a wash whether you pay the tax now or later. This is a critical point, so let me walk through a specific numerical example.

Suppose you’re 40 years old and you have $100,000 in a 403(b) that is earning 5% annually. Further suppose the tax code right now, and for the next 25 years, will be a simple flat tax, with a single bracket that applies a tax rate of 30% on any income.

Now if you leave the money in your tax- qualified account, rolling over tax-deferred until you’re 65, then the 403(b) will have reached a value of about $339,000 when you turn 65. At that point, if you take it all out, you will at that point pay the 30% flat tax, leaving you with a remainder of $237,000.

On the other hand, suppose you rolled it into a Roth IRA, where you pay the tax upfront on the contributions, but then you enjoy the principal and growth without further tax liability. In this case, you pay the 30% flat tax upfront on the $100,000, leaving you with $70,000 to go into your Roth. Then that $70,000 rolls over at 5% annually, reaching a value of $237,000 by the time you turn 65. And then at that point, you can spend your $237,000 free and clear, because you already paid the tax on it.

As this simple example shows, if we hold all of the other moving parts constant, then it is a total wash whether you pay the tax upfront or on the backend. There’s nothing about the “time value of money” that makes it advantageous to be in one type of tax treatment versus the other.

Paying the Penalty

But what about the 10% penalty? It’s true that that’s painful, but on the other hand, I had reasons to suspect that leaving my wealth inside the 403(b) would carry other problems down the road. To name just two: My income will probably be higher in 25 years, and I’m quite sure that marginal tax rates will be higher then than they are now.

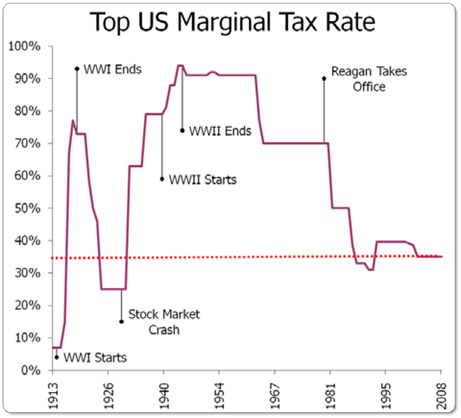

Figure 1. Top Federal Marginal Individual Income Tax Rate, 1913-2008

Source: https://nickgogerty.typepad.com/designing_better_futures/ 2009/06/great-depression-and-top-marginal-tax-rates-since-1913.html

Look at the following chart of the top federal marginal income tax rate in the United States: (Notice that in Figure 1, it stops in 2008. The current tax rate is two percentage points higher than what is shown in the figure.)

Does it look like our current top rate is high or low, compared to its historical levels? It’s true that with globalization and the ease of travel, it’s more viable for highly talented individuals to simply leave the country if things get too onerous. Because of this, governments around the world have had to dial back their individual and corporate income tax rates—just like U.S. states can’t be too outrageous, lest they drive too many people into hospitable states like Florida and Texas.

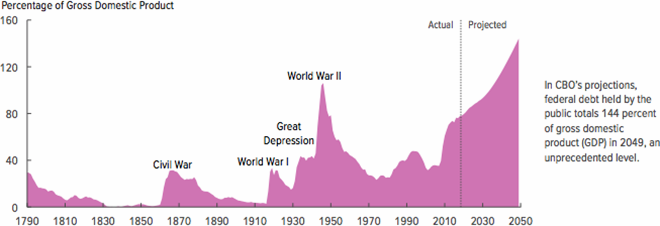

On the other hand, the U.S. government is racking up debt at an extraordinary rate, particularly considering that the official un- employment rate has been so low. Here’s the latest projection from the CBO:

Things are even bleaker when we consider the ludicrous proposals that the current Democratic presidential candidates have been throwing out, including Elizabeth Warren’s nearly $52 trillion (over ten years) takeover of health care—and that’s her number, not a critical estimate.

These considerations helped me decide that the 10% penalty for early withdrawal was the lesser of two evils, compared to the possible tax treatment if I left my wealth in- side the 403(b).

Figure 2. CBO Long-Term Debt Projection, 1790 – 2050

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office1

Now to be sure, the government might come after me down the road anyway, even if right now it promises not to tax the growth in the cash surrender value of my (properly designed and handled) Whole Life insurance policy. Still, on balance I decided that it was more dangerous to leave my wealth in the 403(b) than to take it out.

Conclusion

The world system seeks to control every aspect of our lives, ranging from the food we eat, to what our children learn, to what news we can read even on Facebook. And one of the tightest strangleholds they have is on the financial system. Uncle Sam literally nationalized the creation of paper money, and created the Federal Reserve System to cartelize the commercial banks to allow them to issue their own money, in the form of demand deposits. (Carlos and I explain this in our book, How Privatized Banking Really Works, available at www.Lara-Murphy.com.)

Among other tools, the tax code itself has been designed to herd everybody into officially approved assets. They especially discourage new entrepreneurs, by heavily motivating salaried professionals into locking up their wealth in prison for decades.

Given its track record, do you trust the U.S. federal government’s advice when it comes to fiscal management? You can do what you want, but I decided to cash out my 403(b).

References

- The long-term debt projection in Figure 2 is taken from CBO’s “2019 Long-Term Budget Outlook,” available at: https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-06/55331-LTBO-2.pdf.

Why I Cashed Out My 403(b)

I spend a lot of tIme motIvatIng difficult financial topics by constructing “thought experiments.” In a thought experi- ment, you can only focus on one or maybe two moving parts, while holding everything else constant. This is the way to isolate the impact of the factor you want to understand. However, it means the whole exercise is nec- essarily unrealistic.

That’s why people respond more when someone tells them an actual story about

something that happened, relevant to the topic. Effective speakers know this. A pol- ished preacher, for example, can connect even with a cynical atheist by telling an an- ecdote that illustrates something fundamen- tal about human nature.

For these reasons, I thought it might be

worthwhile to explain why I recently cashed out my 403(b), and used the proceeds to (among other things) buy some more paid- up additional whole life insurance and some Bitcoin. Since my moves fly in the face of conventional financial counseling, I thought it would be useful to explain some of the major considerations in my decision.

It should go without saying that I’m not offering formal investment advice in this essay. I’m just explaining why I did what I did, and letting the reader take any of my remarks into consideration when planning for the future.

Why I Had It

I first should explain why I started out with a decent amount—just so you have some idea, it was more than $15,000 but less than

$75,000—in a 403(b). The simple explana- tion is that part of my compensation pack- age for a spell in academia was a mandatory contribution to the tax-qualified retirement accounts designed for the educational sector. (It’s basically a 401(k) for teachers.)

Now even within this framework, I should mention that I was unusual: I had everything in either gold mining stocks and Treasuries, with the portfolio heavily weighted to the gold. When I first set it up that way, the guy from Fidelity was doing his best to lecture me about the benefits of diversification. (As a PhD economist, believe it or not, I was fa- miliar with this concept.) I told him I had

other assets filling out my desired overall portfolio—here I was primarily thinking of my existing IBC policy—and so my 403(b) was helping to check the box of, “Hedging myself against significant price inflation.” And after my 403(b) appreciated some 20% in the first year, the guy from Fidelity never bothered me again about it.

Liquidity

However, I recently left academia (for family reasons) and am focusing more on entrepreneurial ventures. As such, I wanted to enlarge my pool of liquid funds. I wanted to free myself to focus on the most produc- tive projects, rather than being forced to pick projects that would yield their fruits in the near-term.

In short, I wanted to increase the liquidity of my portfolio, and having a pile of wealth sitting in a 403(b)—when I’m in my young 40s—wasn’t very useful to me. Because of the various enterprises I’ve set in motion, I am not worried about my long-term solven- cy. However, my immediate need for liquid- ity was pressing.

This is why I resolved to withdraw the full amount from my 403(b), in order to bolster my checking account, make a significant purchase of Paid Up Additional life insur- ance, pay down some important debt, donate to the church, and to buy some Bitcoin.

I’m not going to do justice to the explana- tion for why I used the money the way I did.

Carlos and I outlined our economic prog- nosis and why we thought people should acquire actual cash (currency in the home vault), an IBC life insurance policy, and gold/silver coins in the video presentation, “How to Weather the Coming Financial Storms,” available at: https://lara-murphy. com/video0916/.

For an explanation of what Bitcoin is and how it works, see the guide I co-authored with Silas Barta, available at: www.Under- standingBitcoin.us

In the remainder of this article, I’ll try to explain why I decided to get out of my 403(b).

Borrow?

I’m not going to summarize the nuances here, but suffice it to say, if you want to bor- row against your 403(b) or other tax-quali- fied retirement account, there are incredibly

onerous payback rules. Basically, they only let you use your money if you don’t need it.

So although I initially thought I would just temporarily put my gold mining stocks on hold, when I saw the actual rules I decided it made more sense just to liquidate the whole thing, period. I can buy gold mining stocks down the road if I want them again.

Tax Implications

The most obvious objection people raise to my decision is the tax implications. First, I had to pay income tax on my withdrawal. Second, I had to pay a 10% penalty because it was an unauthorized early withdrawal.

Let me just stop and observe, that this is really screwy. It is a sick joke that the Unit- ed States federal government—which is any- where from $40 trillion to $200 trillion in debt, depending on how we evaluate the promises made via Medicare—is spanking people if they have the audacity to try to use their own wealth earlier than the govern- ment deems appropriate. If for no other rea- son than to withdraw consent, I had an urge to get out of this paternalistic system.

However, we can put aside ideological con- siderations and just look at the numbers. If we for the moment set aside the penalty, the simple fact is that—holding everything else, like annual income and the tax code, con- stant—it is a wash whether you pay the tax now or later. This is a critical point, so let me walk through a specific numerical example.

Suppose you’re 40 years old and you have

$100,000 in a 403(b) that is earning 5% an- nually. Further suppose the tax code right now, and for the next 25 years, will be a sim- ple flat tax, with a single bracket that applies a tax rate of 30% on any income.

Now if you leave the money in your tax- qualified account, rolling over tax-deferred until you’re 65, then the 403(b) will have reached a value of about $339,000 when you turn 65. At that point, if you take it all out, you will at that point pay the 30% flat tax, leaving you with a remainder of $237,000.

On the other hand, suppose you rolled it into a Roth IRA, where you pay the tax up-

front on the contributions, but then you en- joy the principal and growth without further tax liability. In this case, you pay the 30% flat tax upfront on the $100,000, leaving you with $70,000 to go into your Roth. Then that

$70,000 rolls over at 5% annually, reaching a value of $237,000 by the time you turn 65. And then at that point, you can spend your

$237,000 free and clear, because you already paid the tax on it.

As this simple example shows, if we hold all of the other moving parts constant, then it is a total wash whether you pay the tax upfront or on the backend. There’s nothing about the

“time value of money” that makes it advan- tageous to be in one type of tax treatment versus the other.

Paying the Penalty

But what about the 10% penalty? It’s true that that’s painful, but on the other hand, I had reasons to suspect that leaving my wealth inside the 403(b) would carry other problems down the road. To name just two: My income will probably be higher in 25 years, and I’m quite sure that marginal tax

rates will be higher

then than they are now.

Figure 1. Top Federal Marginal Individual Income Tax Rate, 1913-2008

Source: https://nickgogerty.typepad.com/designing_better_futures/ 2009/06/great-depression-and-top-marginal-tax-rates-since-1913.html

Look at the following chart of the top fed- eral marginal income tax rate in the United States:

(Notice that in Fig- ure 1, it stops in 2008. The current tax rate is two percentage points higher than what is shown in the figure.)

Does it look like our current top rate is high or low, compared to its historical levels? It’s true that with global- ization and the ease of travel, it’s more vi- able for highly talented individuals to simply

leave the country if things get too onerous. Because of this, governments around the world have had to dial back their individual and corporate income tax rates—just like

U.S. states can’t be too outrageous, lest they

drive too many people into hospitable states like Florida and Texas.

On the other hand, the U.S. government is racking up debt at an extraordinary rate, particularly considering that the official un- employment rate has been so low. Here’s the latest projection from the CBO:

Things are even bleaker when we consid- er the ludicrous proposals that the current Democratic presidential candidates have been throwing out, including Elizabeth Warren’s nearly $52 trillion (over ten years) takeover of health care—and that’s her num- ber, not a critical estimate.

These considerations helped me decide that the 10% penalty for early withdrawal was the lesser of two evils, compared to the possible tax treatment if I left my wealth in- side the 403(b).

Figure 2. CBO Long-Term Debt Projection, 1790 – 2050

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office1

Now to be sure, the government might come after me down the road anyway, even if right now it promises not to tax the growth in the cash surrender value of my (properly designed and handled) Whole Life insur- ance policy. Still, on balance I decided that it was more dangerous to leave my wealth in the 403(b) than to take it out.

Conclusion

The world system seeks to control every as- pect of our lives, ranging from the food we eat, to what our children learn, to what news we can read even on Facebook. And one of the tightest strangleholds they have is on the financial system. Uncle Sam literally nation- alized the creation of paper money, and cre- ated the Federal Reserve System to cartelize the commercial banks to allow them to issue their own money, in the form of demand de- posits. (Carlos and I explain this in our book, How Privatized Banking Really Works, avail- able at www.Lara-Murphy.com.)

Among other tools, the tax code itself has been designed to herd everybody into offi- cially approved assets. They especially dis- courage new entrepreneurs, by heavily moti- vating salaried professionals into locking up their wealth in prison for decades.

Given its track record, do you trust the U.S. federal government’s advice when it comes to fiscal management? You can do what you want, but I decided to cash out my 403(b).

References

- The long-term debt projection in Figure 2 is taken from CBO’s “2019 Long-Term Budget Outlook,” available at: https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019- 06/55331-LTBO-2.pdf.

Why I Cashed Out My 403(b)

I spend a lot of tIme motIvatIng difficult financial topics by constructing “thought experiments.” In a thought experi- ment, you can only focus on one or maybe two moving parts, while holding everything else constant. This is the way to isolate the impact of the factor you want to understand. However, it means the whole exercise is nec- essarily unrealistic.

That’s why people respond more when someone tells them an actual story about

something that happened, relevant to the topic. Effective speakers know this. A pol- ished preacher, for example, can connect even with a cynical atheist by telling an an- ecdote that illustrates something fundamen- tal about human nature.

For these reasons, I thought it might be

worthwhile to explain why I recently cashed out my 403(b), and used the proceeds to (among other things) buy some more paid- up additional whole life insurance and some Bitcoin. Since my moves fly in the face of conventional financial counseling, I thought it would be useful to explain some of the major considerations in my decision.

It should go without saying that I’m not offering formal investment advice in this essay. I’m just explaining why I did what I did, and letting the reader take any of my remarks into consideration when planning for the future.

Why I Had It

I first should explain why I started out with a decent amount—just so you have some idea, it was more than $15,000 but less than

$75,000—in a 403(b). The simple explana- tion is that part of my compensation pack- age for a spell in academia was a mandatory contribution to the tax-qualified retirement accounts designed for the educational sector. (It’s basically a 401(k) for teachers.)

Now even within this framework, I should mention that I was unusual: I had everything in either gold mining stocks and Treasuries, with the portfolio heavily weighted to the gold. When I first set it up that way, the guy from Fidelity was doing his best to lecture me about the benefits of diversification. (As a PhD economist, believe it or not, I was fa- miliar with this concept.) I told him I had

other assets filling out my desired overall portfolio—here I was primarily thinking of my existing IBC policy—and so my 403(b) was helping to check the box of, “Hedging myself against significant price inflation.” And after my 403(b) appreciated some 20% in the first year, the guy from Fidelity never bothered me again about it.

Liquidity

However, I recently left academia (for family reasons) and am focusing more on entrepreneurial ventures. As such, I wanted to enlarge my pool of liquid funds. I wanted to free myself to focus on the most produc- tive projects, rather than being forced to pick projects that would yield their fruits in the near-term.

In short, I wanted to increase the liquidity of my portfolio, and having a pile of wealth sitting in a 403(b)—when I’m in my young 40s—wasn’t very useful to me. Because of the various enterprises I’ve set in motion, I am not worried about my long-term solven- cy. However, my immediate need for liquid- ity was pressing.

This is why I resolved to withdraw the full amount from my 403(b), in order to bolster my checking account, make a significant purchase of Paid Up Additional life insur- ance, pay down some important debt, donate to the church, and to buy some Bitcoin.

I’m not going to do justice to the explana- tion for why I used the money the way I did.

Carlos and I outlined our economic prog- nosis and why we thought people should acquire actual cash (currency in the home vault), an IBC life insurance policy, and gold/silver coins in the video presentation, “How to Weather the Coming Financial Storms,” available at: https://lara-murphy. com/video0916/.

For an explanation of what Bitcoin is and how it works, see the guide I co-authored with Silas Barta, available at: www.Under- standingBitcoin.us

In the remainder of this article, I’ll try to explain why I decided to get out of my 403(b).

Borrow?

I’m not going to summarize the nuances here, but suffice it to say, if you want to bor- row against your 403(b) or other tax-quali- fied retirement account, there are incredibly

onerous payback rules. Basically, they only let you use your money if you don’t need it.

So although I initially thought I would just temporarily put my gold mining stocks on hold, when I saw the actual rules I decided it made more sense just to liquidate the whole thing, period. I can buy gold mining stocks down the road if I want them again.

Tax Implications

The most obvious objection people raise to my decision is the tax implications. First, I had to pay income tax on my withdrawal. Second, I had to pay a 10% penalty because it was an unauthorized early withdrawal.

Let me just stop and observe, that this is really screwy. It is a sick joke that the Unit- ed States federal government—which is any- where from $40 trillion to $200 trillion in debt, depending on how we evaluate the promises made via Medicare—is spanking people if they have the audacity to try to use their own wealth earlier than the govern- ment deems appropriate. If for no other rea- son than to withdraw consent, I had an urge to get out of this paternalistic system.

However, we can put aside ideological con- siderations and just look at the numbers. If we for the moment set aside the penalty, the simple fact is that—holding everything else, like annual income and the tax code, con- stant—it is a wash whether you pay the tax now or later. This is a critical point, so let me walk through a specific numerical example.

Suppose you’re 40 years old and you have

$100,000 in a 403(b) that is earning 5% an- nually. Further suppose the tax code right now, and for the next 25 years, will be a sim- ple flat tax, with a single bracket that applies a tax rate of 30% on any income.

Now if you leave the money in your tax- qualified account, rolling over tax-deferred until you’re 65, then the 403(b) will have reached a value of about $339,000 when you turn 65. At that point, if you take it all out, you will at that point pay the 30% flat tax, leaving you with a remainder of $237,000.

On the other hand, suppose you rolled it into a Roth IRA, where you pay the tax up-

front on the contributions, but then you en- joy the principal and growth without further tax liability. In this case, you pay the 30% flat tax upfront on the $100,000, leaving you with $70,000 to go into your Roth. Then that

$70,000 rolls over at 5% annually, reaching a value of $237,000 by the time you turn 65. And then at that point, you can spend your

$237,000 free and clear, because you already paid the tax on it.

As this simple example shows, if we hold all of the other moving parts constant, then it is a total wash whether you pay the tax upfront or on the backend. There’s nothing about the

“time value of money” that makes it advan- tageous to be in one type of tax treatment versus the other.

Paying the Penalty

But what about the 10% penalty? It’s true that that’s painful, but on the other hand, I had reasons to suspect that leaving my wealth inside the 403(b) would carry other problems down the road. To name just two: My income will probably be higher in 25 years, and I’m quite sure that marginal tax

rates will be higher

then than they are now.

Figure 1. Top Federal Marginal Individual Income Tax Rate, 1913-2008

Source: https://nickgogerty.typepad.com/designing_better_futures/ 2009/06/great-depression-and-top-marginal-tax-rates-since-1913.html

Look at the following chart of the top fed- eral marginal income tax rate in the United States:

(Notice that in Fig- ure 1, it stops in 2008. The current tax rate is two percentage points higher than what is shown in the figure.)

Does it look like our current top rate is high or low, compared to its historical levels? It’s true that with global- ization and the ease of travel, it’s more vi- able for highly talented individuals to simply

leave the country if things get too onerous. Because of this, governments around the world have had to dial back their individual and corporate income tax rates—just like

U.S. states can’t be too outrageous, lest they

drive too many people into hospitable states like Florida and Texas.

On the other hand, the U.S. government is racking up debt at an extraordinary rate, particularly considering that the official un- employment rate has been so low. Here’s the latest projection from the CBO:

Things are even bleaker when we consid- er the ludicrous proposals that the current Democratic presidential candidates have been throwing out, including Elizabeth Warren’s nearly $52 trillion (over ten years) takeover of health care—and that’s her num- ber, not a critical estimate.

These considerations helped me decide that the 10% penalty for early withdrawal was the lesser of two evils, compared to the possible tax treatment if I left my wealth in- side the 403(b).

Figure 2. CBO Long-Term Debt Projection, 1790 – 2050

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office1

Now to be sure, the government might come after me down the road anyway, even if right now it promises not to tax the growth in the cash surrender value of my (properly designed and handled) Whole Life insur- ance policy. Still, on balance I decided that it was more dangerous to leave my wealth in the 403(b) than to take it out.

Conclusion

The world system seeks to control every as- pect of our lives, ranging from the food we eat, to what our children learn, to what news we can read even on Facebook. And one of the tightest strangleholds they have is on the financial system. Uncle Sam literally nation- alized the creation of paper money, and cre- ated the Federal Reserve System to cartelize the commercial banks to allow them to issue their own money, in the form of demand de- posits. (Carlos and I explain this in our book, How Privatized Banking Really Works, avail- able at www.Lara-Murphy.com.)

Among other tools, the tax code itself has been designed to herd everybody into offi- cially approved assets. They especially dis- courage new entrepreneurs, by heavily moti- vating salaried professionals into locking up their wealth in prison for decades.

Given its track record, do you trust the U.S. federal government’s advice when it comes to fiscal management? You can do what you want, but I decided to cash out my 403(b).

References

- The long-term debt projection in Figure 2 is taken from CBO’s “2019 Long-Term Budget Outlook,” available at: https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019- 06/55331-LTBO-2.pdf.